Writing clean code

Introduction

Some people like to code - others do not. Often we write code as a thinking tool, so we can understand a specific problem better. That is well-spent time. But most often, we write code to solve uninteresting analysis problems that we (and others) have already solved before, which is a time sink. As a lab, we want to minimize our total time spent on writing boring code, so we can focus on the interesting problems.

Clean code is easy to read and to understand. It easy to modify and extend. Clean code is easy to test and to debug. Clean code should feel natural and intuitive when you use it. Most often, however, it is not. Too often, it is faster to write your own code to solve a problem than to understand somebody else’s code, making sure it works as you think it works, and then use it. That’s a sign that the original code was not good.

Writing clean code is therefore an essential skill. Like writing clear papers, there are a lot of skills, techniques, and habits that can all be learned. Mastering them it will save you (down the line) and others (immediately) a lot of time and frustration. It allows our lab to do more complicated things faster. Writing clean code requires clear thinking about the structure of the problem, about data organization, and about the scientific question itself. Writing clean code is not just a service to others, it will make your own science better.

Spotting bad code

Don’t worry - of course your code is good. It works, right? You understand what it does and how to call it? It does exactly what you want it to do in one line? So it must be good - no? Unfortunately, you are likely the least qualified person to judge the quality of your code.

A better judge of your code is a new student to the lab who wants to build upon your project. It’s the person that is trying to replicate your paper. It’s the person that wants to use your analysis technique. In sum, you only have written good code, when other people are using, it really like you because of it. So even if you already write pretty clean code - it can always be better. And that takes work and attention to detail.

Here are some signs of code that requires improvement:

- You find yourself writing the same kind of code over and over again

- You find yourself copy-pasting code from one project to another

- You have to look up the name, input or output arguments of a function you wrote

- You discover that you have written two functions that do very similar things

- You know that you have solved this problem before, but you cannot find the code or remember how you did it

- Half a year later, it takes you a while to figure out what the code actually does

- Sharing your code online upon publication fills you with dread (or you secretly hope nobody will ever look at it)

- Other people in the lab who do very related things write their own code, rather than using yours

One principle to improve your code is code review. Companies like Google and Facebook have a very strict code review process. Every line of code that is written is reviewed by at least one other person. In the lab, we do not have the resources to do this - at least not for all the code that is written. But in general, show you code to others. Ask them to use it. Improve your code based on their feedback. And if you see somebody write bad code, tell them and help them to do it better.

Different types of software projects

Not all code requires the same level of scrutiny and care. I think we can distinguish the following levels of code projects:

| Level | Description | shared with | Version control | Documentation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Private | Your dirty underwear | Nobody | - | - |

| 2. Project | Notebooks, workflows, and functions for a single project | A few people - public upon publication | Github | Readme |

| 3. Internal | Functions and classes that benefits multiple projects | Mostly lab and close collaborators | Branch control | Readme + Sphinx docs |

| 4. External | Software packages we support for the community | SUIT, RSA, PcmPy, nitools, etc | Code review, releases, PiPy packaging | Readthedocs |

Many projects and repositories contain code at different levels. Keep them separate. A good practice is to place general tools (classes and functions) in modules at the root of the directory, so they can be easily imported. Place project-specific code in a scripts or notebooks directory. If you find that you want to use the same code in multiple scripts, it belongs in a module. Place your dirty underwear in a appropriately named directory - scrapheap or scratch comes to mind.

Meaningful Names

Name things in a way that makes clear what they are. There are many rules on naming out there, but remember that the main point is to make the code easily readable. The better your names are, the less comments you need to write.

Variables

Variable names should tell the reader what the variable is. median_rt is a better name than mrt. condition is better than c.

On the other hand, long variable names do not make the code automatically more readable. number_of_trials_per_block maybe very clear, but it makes the lines of code very long. When using shorter forms like n_trials, make sure that you use these forms consistently. Do not mix n_trials, num_conditions, number_of_blocks, and N_runs in the same project.

Some guides say to avoid single-letter variable names. I disagree: Local variables in loops can definitely be single letter - for example i and j for indices. for i,pid in enumerate(participant_id): is perfectly clear and makes the code within the loop more readable.

Variables with defined mathematical notations can also be single letter. design_matrix maybe more explicit than X. But I find

inv(X @ inv(V) @ X.T) @ X.T @ inv(V) @ Y

much more readable than

numpy.linalg.inv(design_matrix @ numpy.linalg.inv(covariance_estimate) @

design_matrix.T) @ design_matrix.T @

numpy.linalg.inv(covariance_estimate) @ activity_data

By convention, we use capital letters for matrices / tensors and lower case letters for vectors / scalars. When you use short forms, just make sure the meaning of the variable is defined in the comment section of the code.

Functions

Where variable names should begin with a noun, function names should start with a verb. get_data retrieves some data. set_param sets a parameters. compute_t_stats computes a t_statistics. func1, my_secret_weapon, or tmp are not good names.

Classes

Classes describe Objects, who have both features (attributes) and behaviors (function). Class names should be nouns, start with a capital letter, in the lab code we use CamelCase for them (where otherwise we use understroke). So Nifti1Volume is a good class name.

Often you have a whole collection of classes, all inheriting from a superclass. It is good practice to start the class name with the superclass. AtlasSurface and AtlasVolume is good, as this naming works well with tab-completion: By typing Atlas<tab> you can see immediately all available Atlas classes. While SurfaceAtlas and VolumeAtlas roll better of the tongue, tab completion does not work well.

Projects, Repositories and Packages

Projects are hard to name. Make sure that the project name you choose is unique and will make clear to sombody in the lab what it is. PhD_Experiment_1 obviously is not very descriptive.

We use a abbreviated form of the project name as an identifier for functions, datafiles, and directories. So the tendigit mapping project contains experiments td1-td5.

For repositories for general use (level 3 and 4), you may want to check if the name is already taken on PiPy, the Python Package manager. Ideally your repository and the package have the same name. Sometimes this is not possible, so the repository nitools has to be installed as pip neuroimagingtools, because nitools was already taken.

Do not be afraid of renaming

Naming everything clearly and consistently is hard. Make it a habit to inspect your naming convention from time to time. Is it consistent? Are they readable? Do they make sense? If not, rename them.

Editors like VSCode make it easy to rename variables and functions across multiple files - but check the section of backwards compatibility.

Comments

If you have to write very long comments to explain how your code works, it maybe because your code is not very clean. Ideally, code should be self-explanatory.

In the beginning of each function should be a doc-string that explains what the function does, and defines the input and output arguments. If you follow the following convention (google docstrings), you can build documentation for Python functions automatically using sphinx and readthedocs (see Documentation).

def my_function(data,

anatomical_struct='cerebellum',

labels=None):

""" Say what the function does followed by a blank line.

Args:

data (np.array):

n_vert x n_col data

anatomical_struct (string):

Anatomical Structure for the Meta-data. default: 'Cerebellum'

labels (list):

Numerical values in data indicating the labels. default: np.unique(data)

Returns:

gifti (GiftiImage):

Label gifti image

info (dict):

Dictionary with meta-data

"""

Comments within the code should be used sparingly. Structure different steps in the code with blank lines.

Data Structures

So far we have talked about the Micro-structure of code - how to name things, how to comment. The most important difference between good and bad code often lies in its Marco-structure. Marco-structure of data analysis project consists of Data Structures, and the processes between them.

Bad code writing often starts with bad decision about the underlying data structures. If you have a lot of code that wrangles your data from one structure into the next, you probably made some bad decisions about how to store and organize your data.

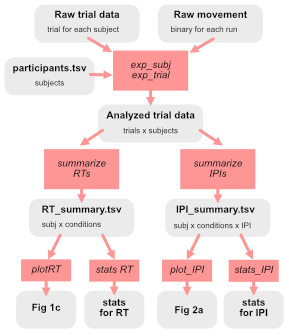

An important technique when planning your analysis code is to draw a diagram of how your code goes from the raw data to final figures and statistical results. The figure shows an simple example from a behavioral experiment. Data structures (and the associated files) are shown in gray, workflows (see below) are shown in red.

In this simple example, the raw data consist of three type of data structures:

- a

participants.tsvfile with one row per participant withparticipant_id,sex, andageinformation + any other information that is relevant for the analysis (other questionnaires, group assignments, etc). - a

<exp>_<subj_id>.datfile with one row per trial, saved separately for each subject. - a

<exp>_<subj_id>_run<num>.movfile that holds a raw kinematic data for each trial.

The first step is a workflow that loads all the raw data and produces an overall analysis file with a row per trial (and all subject combine). This file then is used to produce summary tables with on entry per subject and condition - one for the RT results, one for the inter-press-intervals. These two are stored in separate files, as they required a different number of rows. Finally, each figure panel and statistical analysis is generated. This data flow structure is very clean and transparent. The advantages are:

- We have the absolutely smallest amount of data files - no data structure is duplicated

- Workflows only use the the data structures that they absolutely need

- There is only one replicable way to go from data structure to data structure

- The data can be easily be shared at 3 levels

- the tabular data underlying each figure and stats reported

- the preprocessed trial-based data

- the raw data

- Each level is sufficient to reproduce the final results that depend on them

- It is clear how each data structure was generated - when an error is detected it is clear which part of the analysis is effected

It is likely that when you draw the diagram for your project, it will be much more complicated. Your goal is to reduce the complexity of this tree as much as possible. Common problems and solutions are:

| Problem | Solution |

|---|---|

| Dead or depreciated data structures clutter the analysis code and data directories | clean up |

| Alternative data structures for overlapping purposes | Generate one common data structure |

| You data structures are nested to combine scalar data and large binary files | Keep separate data structures separate |

| Error trials are removed early in the analysis, so you need to go back to the raw data to analyze them | Include all trials in the second stage, and label them with a ‘error’ column |

| Your processes overwrite data structures | Avoid loops in the graph and make sure to include necessary later steps in the initial process that generates the data structure |

| Workflows depends on a lot of different data structures | Data structures should include all necessary data for subsequent analyses |

| Workflows need to load large data structures to extract a small amount of information | Data structures should include only the data are necessary for subsequent analysis |

Important data structures are stored on disk as files. In general, you want to choose file formats that are established in the lab and the community.

- Data frames stored in .tsv files. Generally, it is preferable to store the data frame in a long format (one column per dependent variable, and condition coded in another), not a wide format (a separate column for each condition).

- Nifti, Gifti, Cifti files for Neuroimaging data

- BIDS-compatibility where practical

- For custom binary file formats, .pickle and .mat files do not travel well between analysis platforms. Use HDF5 instead if necessary.

Workflows, Functions and Factorization

Workflows are processes that transform one data structure into the next. When you just start programming, you will likely write a script to do this. Let’s look at a typical example of this in pseudo-code, which fits a model to a specific subject’s data:

subj_name = 'sub-01'

model = 'model-specific'

# 1. Get the requried data file name

file_name = f'{subj_name}_task-<exp>_run-01.dat'

.... # Code that deals with different directory structures and file formats

# Load the data file

...

# Get the model

model_file_name = ... # Some more complicated rules about naming of the model

# Load the model

...

# Do some preprocessing on the data

...

# Generate some starting values for the model fit

...

# Loop over model fits until convergence

...

# Select the best fit

,,,

# Save the results into a specific file

out_file_name = ... # Some more complicated rules about naming / location of the output file

save_results(out_file_name)

Scripts are often long, hard to read, and not very reusable. So it is clearly time to refactor the script into different functions. But there are many ways to do this. The first step is to identify the elemental operations that your code does. This already pretty clear in the above example. Each of these elemental operations should be a function. The principle for these functions should be:

- Elemental Functions should do one thing, and one thing only

- They should do this thing well

- Ideally you make these functional reusable for other projects - so separate the project-specfic naming and file handling from the actual data processing

- Inputs arguments to a function should be as few as possible. This is the Mafia-principle of coding: The guys that do the job on the street really should only know enough to do their job, but no more.

Once you achieve this, you should be able to make your process also into a function that may look like this:

def fit_model_to_individual_data(subj_name, data_type, model_type,N-iter=20):

data_file_name = get_data_file_name(subj_name, data_type)

data = load_data_file(data_file_name)

model_file_name = get_model_file_name(model_type)

model = load_model_file(model_file_name)

data = preprocess_data(data)

for i in range(n_iter):

starting_values = generate_starting_values(model)

params[i] = fit_model(data, model, starting_values)

best_fit = select_best_fit(fits)

result_file_name = get_result_file_name(subj_name, data_type, model_type)

save_results(result_file_name)

Yoy have achieved nirvana: Your code is so clean and readable that (except for the function definition), it does not require any comments. Of course it could be further imporved (see classes), but you are off to a good start. On top of this process-function, you finally will have scripts that call this process for a particular set of models and subjects.)

info = pd.read_csv('participants.tsv',sep='\t')

model = ['model1', 'model2']

for m in models:

for subj in info['participant_id']:

fit_model_to_individual_data(subj, data_type, m)

What makes this code readable and easy to understand:

- You have three levels of functions: Elemental functions, process functions, and scripts. Each level calls only the subordinate level.

- Elemental function have one single function and an appropriate name

- They only receive the information they need to do their job

This is easy, right? But it is actually often very hard to achieve. One common problems that occur is that code is wrapped uneccessarily. For example, you maybe tempted to combine certain steps in the process function. On the postive side, your code will be shorter and may have less repetition of code. On the negative side, you now have 4 levels of code. So for a new person to figure out what is going on, they have to go through all those levels. You are also adding a lot of lines of code just to pass the arguments from one function to the next. A good practice is to determine the call depth of your code and ensure that it is as small (shallow) as possible, while still being readable.

Another problem is that you violate a clear hierarchical structure of the code. Process function calling other process functions. Elemental functions call other elemental functions, or even process functions. Elemental functions that can’t be reused, as they make specific assumptions about filename / directory structure. In all these cases, take some time and refactor your code.

Classes

Object-oriented programming is an advanced and powerful tool for designing clean code. If you use Python, any variable you are using is already inherently an object. In Matlab, object orientation is a clear afterthought.

When should you define a new class? Usually I use classes only when all of the following criteria are met:

- You have things (objects) that have multiple data members (attributes)

- You have multiple functions that operate on the similar data members

- You have multiple types of objects that all are behaving in a similar way, but have some differences

If only the first condition is true, you should use a dictionary. If the second case is true, you will collect these functions into a module. However, the power Object oriented programming comes in when the third criterion is also true.

A classical example is the definition of different types of models, each of which has certain parameters, and a function that fits the model to the data. Let’s look at an object oriented version of the model fitting example above.

class Model:

def __init__(self, name, params):

self.name = name

self.params = params

def generate_starting_values(self):

self.params = ....

def fit(self, data):

...

def save(self, file_name):

...

class Model1(Model):

def __init__(self, params):

super().__init__('model1', params)

def fit(self, data):

...

def fit_model_to_individual_data(subj_name, data_type, model_type,N-iter=20):

data_file_name = get_data_file_name(subj_name, data_type)

data = load_data_file(data_file_name)

data = preprocess_data(data)

for i in range(n_iter):

model[i] = get_model(model_type)

model[i].generate_starting_values()

model[i].fit(data)

best_fit = select_best_fit(model)

result_file_name = get_result_file_name(subj_name, data_type, model_type)

mdoel.save(result_file_name)

You can see that the code is a bit longer than the non-object oriented version above. However, the advantage really arises when you also define an Model2 and Model3. In standard programming, you would need to write:

if model_type == 'model1':

params[i] = fit_model1(data, model, starting_values)

elif model_type == 'model2':

params[i] = fit_model2(data, model, starting_values)

elif model_type == 'model3':

params[i] = fit_model3(data, model, starting_values)

and again for saving, prediction, etc. With Object oriented programming, you can just write:

model.fit(data)

And Python will select the right fitting routine, depending on the object type of model.

Computational Efficiency

Backwards Compatibility

Clean up!

Have you ever worked on a construction site? If you have, you know that the last half hour of every working day is dedicated to cleaning up your tools remove any debris, and make sure that the things you build are clean. Otherwise people get injured tomorrow.

You should do the same every day with your code before you stop working.

- Delete all unnecessary files and directories that you produced

- Delete all code that your tried out, but did not work

- Move things you want to keep for later into a ‘depreciated’ directory

- Remove all dependencies that are not used anymore (import)

- Remove all variables that you are not using anymore

- Make sure the things your produced live up to the standard we expect (naming, structure, comments, etc)

- Commit you code to git

Read more

- Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship by Robert C. Martin